Story of Mindform

Mindform is more than just a game. It is a creation that has emerged from four years of dedicated development by the team at GameTrain Studios. Now, as the game is about to be released on Steam, it’s intriguing to consider what this First Person Climbing game signifies for the esports world and the realm of game development.

This project, which began as a concept, has morphed through various stages over the years. The process encompassed endless meetings, brainstorming sessions, and the continual reevaluation and refinement of concepts. This journey, in many respects, mirrors the experiences of someone venturing into the competitive esports arena – it’s a perpetual cycle of learning, adapting, and enhancing.

GametrainStudio’s

GameTrain Studios, an indie game developer from Rotterdam, is the result of a meeting between various professionals at DreamHack Rotterdam in 2019. This studio merges the passions and skills of gaming enthusiasts, software developers, and a sports professional.

The founding of the studio naturally stemmed from the collaboration between Cas and Jeroen from Vorteq, who bring their expertise in software development, Sander from Decade IT, with his background in game development, and Timo from Sportbrein, who adds experience from the world of professional sports. This mix of experiences forms the foundation of the studio.

Contributions from other individuals like Joeri, Anna, and Dirk in meetings and design processes further enrich the team. Additionally, collaborations with external parties such as illustrator Roy Droog and filmmaker Ramon Giessen, as well as the academic insights from Finn Tempelaar and Jenny Schultz from the University of Twente, Barbara Huijgen of the University of Groningen enhance the diversity and richness of GameTrain Studios’ projects. More on this later.

The Idea

The Idea In traditional sports, such as soccer, hockey, or basketball, it’s common for ambitious athletes to head to a club with their sports bag for training and development. There, they physically meet their coaches, who help them grow further. The combination of guidance, perseverance, and talent provides the opportunity to reach the top, where attention and success await. We increasingly see this trend in the world of esports, with growing opportunities for talents to meet and receive coaching.

However, there is a significant group of home gamers who dream of success in esports but don’t quite know how to realize this dream. They experience frustrations such as losing, making no progress, becoming quickly irritated, losing the joy in gaming, and uncertainty about how to improve themselves. These issues can lead to an early dropout.

Our goal is to help precisely this group of aspiring talents. We aim to provide them with the tools and guidance necessary to make their dreams come true and reach the top of the esports world. This is our mission statement, written from the perspective of Simon Sinek’s Golden Circle.

Why

Creating E-Sports Legends

How

By providing a learning environment for continuous improvement.

What

The game is a fun and effective addition to the daily routine that is based on proven principles already used in Gaming, Science, Cognitive trainers and (e-)Sports.

Research

Research In our mission statement, we emphasize the importance of principles backed by scientific research. An example of this is the study by Nagorsky and Wiemeyer, who looked into the crucial competencies for a professional esports player./doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0237584

Their study reveals that a wide range of competencies affects the development of an esports player. For instance, specialized AIM trainers such as AIMLABS are specifically designed for training sensorimotor control and cognitive skills. The diagram provides a clear picture of which competencies are truly important for aspiring esports players. Additionally, the esports landscape is diverse, including various game genres such as fighting games, real-time strategy (RTS), traditional sports games, and multiplayer online battle arena games (MOBA). For each game/genre, the competencies are again slightly differently defined.

Early Years

Our initial ideas focused primarily on two key areas: sensorimotor control and cognition. Timo, from Sportbrein, gained insights into methods to improve working memory and other executive skills through contact with cognitive trainers, using techniques such as Cogmed and, in the sports world, NeuroTracker. An example of a brainstorming session resulted in an exercise that trains perception, attention, working memory, inhibition, and reaction speed in an adaptive manner. See the following image:

In this exercise, circular discs, each with a letter or mouse click, move, and the player must quickly respond when they enter a green-colored circle, or suppress an impulse when it turns red. The adaptability lies in the speed of movement and the fact that the discs can disappear behind a black bar, requiring prediction of where the circles will go.

We adjusted and further developed our plans weekly, resulting in four categories: Motor Training, Cognitive Training, Game Sense, and Mindset. Seventeen ‘mini-games’ were elaborated one by one, all with scientific justification. Of course, all these ideas were based on hypotheses that needed to be validated later to see if they were indeed effective, especially in terms of transfer to the ‘real’ game.

This is crucial, as the ultimate goal is for players to improve in the game they love most and in which they want to excel. This question made us wonder if we were on the right track, or if our ideas might not have the intended effect.

Mindsetswitch

We quickly realized that it would be a challenge to optimally assist players with our cognitive mini-games. Although a transfer effect was theoretically justifiable, we encountered issues, including the enjoyment of our game. Julian Nagelsmann, the head coach of the German national football team, adheres to the principle that boredom impedes learning. This insight, together with feedback from our target audience, made it clear that mini-games focused on cognition were not the solution. But what then?

Through this process, ‘Mindset’ remained as a core component. ‘Mindset’ is an important theme in (sports) psychology. American psychologist Carol Dweck from Stanford University identified two types of mindsets: fixed and growth. Individuals with a ‘growth mindset’ believe that abilities are developable and that anyone, with the right guidance and effort, can improve their skills. Failure simply means that more practice is needed. People with a ‘fixed mindset’, on the other hand, believe that abilities are set and often avoid activities they are less skilled at to evade mistakes and negative feedback.

Another important concept is ‘locus of control’. Locus of Control derives from Rotter’s social learning theory from 1954. It concerns the feeling of control over events and situations in your life. People with an internal locus of control believe they have control over what happens and take responsibility for their actions. People with an external locus of control see their situation more as the result of external factors.

These theories are often cited in science, especially in sports. But what if we could translate these theories into a fun game? However, a ‘growth mindset’ is more of a cognitive concept than a skill, reflected in a person’s attitude and values, not necessarily their behaviors. It is widely recognized that changing behavior does not always alter the underlying attitudes and beliefs that are crucial in developing a growth mindset.

ASE Model

To clarify our own insights, we decided to thoroughly analyze the ASE model. This model, which stands for Attitude, Social Influence, and Self-Efficacy, provides a psychological framework for understanding behavior formation and change. The model has helped our team grasp how behavior change occurs. The attached photo shows that various factors influence the behavior of an esports player. Attitude concerns personal beliefs; a positive attitude, such as believing in the importance of hard training and skill development, is crucial. Social Influence includes perceptions of what significant others think of this ambition, where support from family, friends, and the gaming community can strengthen the intention to become a pro-esports player. Self-Efficacy is about confidence in one’s ability to take the necessary steps, including belief in personal skills and the ability to face challenges.

While there is criticism of the model, such as not accounting for the player’s emotions, it provides us with a clear overview of the influences on behavior. Even during the further production and testing phase, the ASE model proves to be a useful reference to check if we are hitting certain elements, with the ultimate goal of effecting behavior change beyond Mindform.

ACT

The core question remains, however: how can we best assist players? How do we ensure that concepts like Mindset and internal locus of control are integrated into a game effectively and in a fun way, so that it’s not only challenging and educational but also applicable in other games that the player enjoys? Especially when emotions come into play. Pressure or fears of failing can be a significant barrier to attitude. The first step was to return to the drawing board to explore which theories could help us enhance the potential transfer of this cognitive concept.

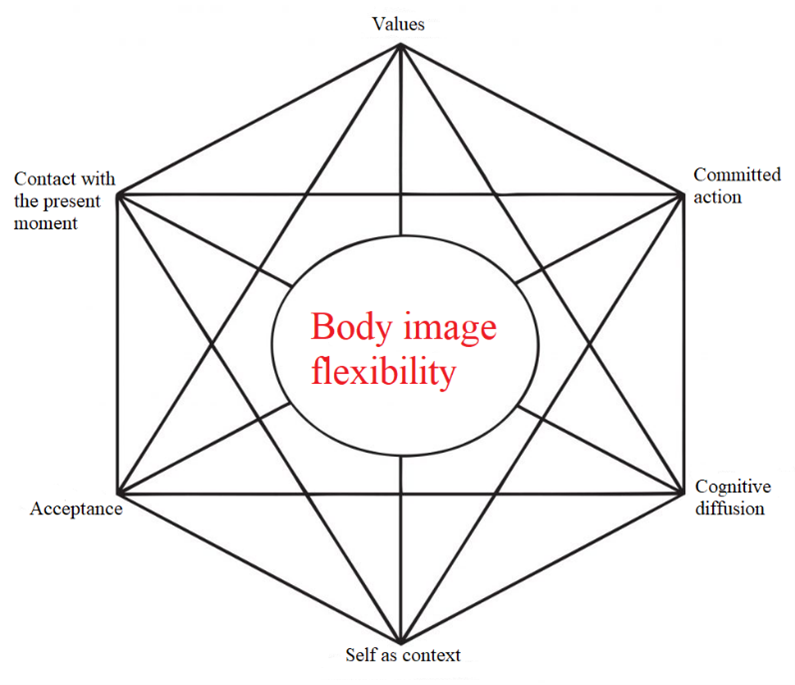

Mindfulness and acceptance-based approaches, such as ACT (Acceptance and Commitment Therapy), are gaining popularity within (sports) psychology. While performance optimization in sports often focuses on ‘feeling good’ and prompts individuals towards behaviors that reduce or eliminate unpleasant (and performance-disrupting) thoughts and emotions, ACT aims to achieve the opposite. For example, an e-sports player under pressure during a critical moment in the game may play defensively to avoid the fear that arises from taking necessary risks. In ACT, the goal is not to help athletes suppress these emotions but to accept them, including both positive and negative thoughts and physical states of arousal, while remaining attentively and behaviorally engaged in the task at hand. The core idea also revolves around being in touch with personal values and the present moment (Hendriksen, Hanse, & Larsen, 2019).

inspiring games

The theoretical foundation for Mindform had been established, but now the question remained of which game mechanics we would use. Three games, in particular, inspired us:

The Stanley Parable The Stanley Parable is a first-person adventure game. The story revolves around Stanley, a simple office worker whose colleagues have mysteriously disappeared. As the player, you take on the role of Stanley, making choices while simultaneously having choices taken from you. The game ends and yet it doesn’t. Contradictions follow one another, and the rules of how games should work are broken and re-broken.

Superliminal Superliminal is a first-person puzzle game centered around perspective and optical illusions. The puzzles contain unexpected elements and often force the player to change perspectives to wake up from a dream. The game conveys the message that the problem often lies not in the unsolvability of problems but in our fear of failure that prevents us from seeing problems from a new perspective.

Getting Over It Getting Over It is an arcade game where you climb a mountain using a hammer. The game’s physics play a significant role, and it’s a challenge to see how far you can get before frustration sets in. The game is extremely difficult, and any mistake can send you back to the beginning. It tests the player’s Stoic perseverance: do you succumb to frustration, or do you persist?

All these games have a psychological element. The Stanley Parable influences player behavior through a narrator. Superliminal presents an engaging story in a dream world, while Getting Over It challenges the player with its frustrating gameplay. Each game offers unique insights and approaches that can inspire us in the development of Mindform.

Concept & Story

We are now almost over 2 years into the project, and it’s time to take stock of exactly where we stand. Our current focus is on home gamers who dream of a career in esports but are uncertain about how to realize this dream. They face frustrations such as losing games, stagnation in progress, becoming quickly irritated, losing the joy of gaming, and uncertainty about their own development. These challenges can lead to prematurely giving up on their ambitions.

Furthermore, certain competencies are crucial to reach the top of the esports world, specifically ‘Emotions, Motivation & Willpower’ and ‘Personal Competencies’. We use the terms ‘Mindset’ and ‘Internal Locus of Control’ to highlight these concepts, although they are not directly visible as behavior. The ASE model has provided us insight into the factors that influence behavior, though it overlooks the emotions of players. Additionally, we apply techniques from ACT to deal with emotions arising from failure, pressure, and other influences.

We have drawn inspiration from various games, such as The Stanley Parable, Superliminal, and Getting Over It, with the goal that players experience Mindform, have fun, learn, and apply this knowledge in the games where they wish to excel.

The result is a game that tells the story of a player making a metaphorical climbing journey to the trophy in the stadium, all within their own psyche. This is supported by various narrators who provide context in the form of a ‘coach’ and an ‘enemy’. The coach acts as a motivational and educational guide, while the ‘enemy’ introduces conflicts and doubts that the player must ‘overcome’ for growth. The climb is not easy, where failing and frustration is very likely, something naturally comparable to someone pursuing a career in elite sports.

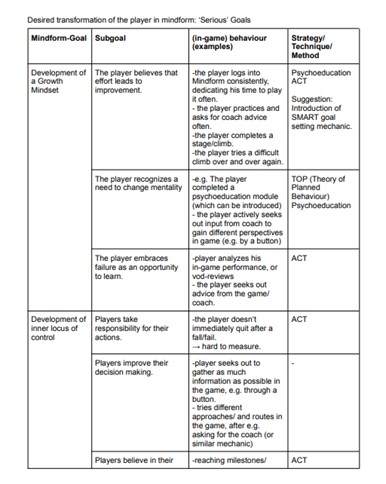

Desired Transfer Effect

As mentioned above, we aim to solve various problems that ambitious esports players encounter. But what are we hoping for, or rather, what desired effect do we hope to see in players who have spent many hours playing Mindform? Within the context of the desired transfer effect, it’s crucial to recognize that many of the set goals are focused on attitudes and cognitive skills, and not directly on observable behavior.

Therefore, it is important to identify which specific in-game behavior reflects these attitudes and cognitive skills. For instance, the sub-goal of ‘perseverance in the face of challenges’ can become visible in the form of persistence, such as when a player repeatedly tries to complete a difficult section of the game, regardless of the number of times they fail.

Additionally, embracing failure as a learning opportunity can manifest in behaviors such as analyzing one’s own gameplay experiences, including failures, or actively listening to feedback from the coach.

By making these connections between goals and concrete behavior, Mindform can more effectively support players in making the transition from cognitive and attitudinal development to practical application in their gameplay outside of Mindform.

It’s important to emphasize that all of this is still hypothetical; in the future, targeted research will be conducted to see if this actually occurs.

Researcher Jennifer Schulze from the Esport Team Twente has created a table in her paper, “The Coach And Enemy Voice In Mindform: A Psychological Perspective,” which outlines each goal along with the associated behavior in combination with a technique.

Coach and Enemy

To convey the above (sub)goals, a special role is reserved for the narrators. The coach has the opportunity to ‘shape’ behavior in the initial phases (e.g., by rewarding certain actions with small improvements focused on performance and effort, not outcome). This approach is also supported in the literature (e.g., Mueller & Dweck, 1998), which found that performers who received feedback focused on effort (e.g., ‘good try!’) performed better than those who received feedback focused on abilities (e.g., ‘you’re talented!’), especially after failure. Moreover, it has been shown to increase perseverance and enjoyment of the task, which is important for the direction and goals of Mindform.

Feedback or coaching can increase motivation, as long as it is sincere and behavior-dependent. Whether it’s praise or criticism, feedback must be linked to specific behavior or a set of behaviors. To give an example: a player in Mindform struggles to learn how to correctly swing to another grip. Since specific feedback must be linked to performance, the coach here has the opportunity to teach the player how to correctly perform the skill. Instead of saying: ‘well done, keep it up’, the coach narrator says: ‘make sure you place your hands slightly on the side of the grip to more easily reach the other grip when you swing’. This shows sincerity and strengthens the connection with the player, as they feel the sense of honest help and develop trust (which is important for the introduction of later skills and principles).

Performance feedback can usually take two forms: motivational feedback and instructional feedback. While motivational feedback (e.g., ‘keep going, you can do it, get through it!’) is usually given to facilitate performance, inspire effort, and create a positive mood, instructional feedback provides information on how an action/behavior should be performed, the level of skill that needs to be achieved, or the current level of skill of the player in the desired skills or activities. This type of feedback is crucial to integrate into Mindform, as some of the skills are very complex.

In “Mindform”, we’ve conceptualized an Enemy that embodies the negative subconscious voice. As in other games or movies, it’s common to have an enemy or villain that needs to be “defeated”. Based on principles from John Truby’s “The Anatomy of Story: 22 Steps to Becoming a Master Storyteller,” antagonists play a crucial role by providing conflict, propelling the story forward, and challenging the protagonist’s transformation. In our game, this antagonist represents the subconscious voice many players struggle with, discouraging them from persevering and sowing doubt about their potential.

However, there’s also a significant danger we’ve considered: The enemy voice can, for example, be labeled as criticism and thus act as punishment. Although the behavior that elicited this ‘punishment’, ‘falling’ (which could be a mechanical error), is not necessarily related to the player’s current attitude. Imagine a player who shows initial signs of a growth mindset thinking to themselves, ‘although this climb is difficult, I want to take on the challenge’. The player then attempts the climb but falls and is punished with the enemy voice. This can then be experienced as demotivating and, as a result, hinder the behavior of ‘climbing’, or worse yet, ‘attempting to climb’.

In the development process, a balance was sought between an ‘enemy’, where a player can draw motivation to optimally motivate themselves, but at the same time

Game Development

For the entire game development, we used Unity. Take, for example, the screenshot below from the first phase of development: a simple box, with a couple of ‘hands’ and a climbing wall. From there, we continuously tested and iterated, always with the goal of getting a little better. We deliberately chose a Low Poly style, as this style gives the game a quite unique visual appeal and is less demanding in terms of graphics, while also shortening the development time. Blender was then used for designing most of the graphic elements in the game.

Playing in the Brain

The game takes place within the player’s brain, where in the introduction scene, you are literally sucked into your own brain by a ‘brainblast’: Within the game itself, the neurons are also prominently visible in the air. Playing within one’s own brain offers various advantages. It opens the door to a fantasy world that doesn’t necessarily have to align with reality. Moreover, the game conveys an important message: the brain plays a crucial role in the decisions you make, in both behavior and attitude. Furthermore, it aims to convey the idea that brains and neurons can be well-trained. It also offers the opportunity to incorporate an unconscious voice that acts as an ‘enemy’. This can help players recognize this voice and learn to keep it at bay, even in other situations or games. This is at least our hope as developers, although we cannot yet demonstrate this with certainty!

Kill Your Darlings

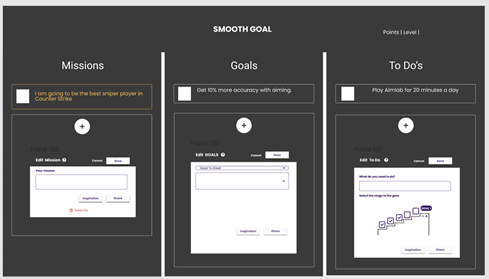

Reaching the top is a challenge full of falls and recoveries, ironically just like developing a game. The described processes are very recognizable. ‘Kill Your Darlings’ means that sometimes you have to give up something you have developed and produced. This is frustrating but essential to stay focused on what is truly important. Take ‘Goalsetting’, for example, an element that we removed from the first version of Mindform. This sports theory is crucial for athletes. Without clear direction, goals, and concrete actions, little progress is made. Our plan was to allow players to formulate their own goals, which they have outside of Mindform, within the game. Upon reaching a goal, they could place a ‘flag’, similar to a flag on the summit of a mountain – a common practice among mountaineers. This way, we wanted to link Mindset and Internal Locus of Control to Goalsetting.

Another idea was to allow players to share their goals with the community, to provide insights into different goals. Although we initially scrapped Goalsetting, this theory is important and we plan to reintegrate it at a later stage. This is just one of the many examples that have been removed from the Game.

The Coach And Enemy Voice In Mindform: A Psychological Study

Throughout the production of Mindform, we established several valuable contacts with different knowledge partners. This is how we came into contact with Finn Tempelaar and Jennifer Schultze, prominent figures within the Esport Team Twente. Finn is an esports player in League of Legends, and Jennifer is a psychologist attached to the team. Both have provided Mindform with fantastic feedback, not just in terms of mechanics and aesthetics but also on a theoretical level. Jennifer, with her expertise, wrote a paper titled “The Coach And Enemy Voice In Mindform: A Psychological Study”. This 50-page document clearly explains the requirements the narrators must meet to have maximum impact on the players. Much of this information has been incorporated into Mindform and included in this story. It is a substantiated contribution that has been integrated into the game. In a later phase, Finn and Jenny will conduct scientific research on the transfer effect of Mindform. With Mindform, we hope to create a game that genuinely helps players improve, thanks in part to the contributions from Jennifer and Finn.

Early Release & Disclaimer 😉

The project has been running for several years now, and we have set high ambitions. Are these objectives realistic? Absolutely, but we are also aware that there is still a lot to be done to perfect everything. With the launch of the Early Release, we hope to build a community that can further assist us in this process. This also comes with a small caveat: we hope to have created a fun and educational game, but of course, we can’t offer any guarantees. Additionally, we aim to conduct scientific research into the effectiveness of Mindform together with our partners.

Big Shout Out!

We would like to extend our profound appreciation to everyone who has played a pivotal role in the development and success of Mindform. Our heartfelt thanks go out to the dedicated team at GameTrainStudio, with a special mention of Joeri Wagner for his invaluable early insights into the gaming industry. We are also grateful to Dirk, Anna, and others who have significantly contributed to the game’s development and enhanced its visual appeal with their graphic design expertise. Our acknowledgment would be incomplete without mentioning the exceptional graphic contributions from Roy Droog. Additionally, our gratitude extends to Jenny and Finn from Esport Team Twente for their insightful contributions. Lastly, our sincere thanks to Ramon Giessen Film Productions for enriching the game with outstanding video content.

In Summary

We hope this extensive blog has given you a clear picture of Mindform, from the initial idea to the concept and further developments. We are aware that there is still a lot of work to be done to make the game as optimal as possible. But for now, we hope you have become excited to start playing Mindform! For more information about Mindform, or if you want to help us, join our Discord server!

MindformTeam

Sources (Article)

- CogniSens Athletics. NeuroTracker [Software]. Available from: http://www.neurotracker.net/

- Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. Random House.

- Foddy, B. (2017). Getting Over It with Bennett Foddy [Video game]. Bennett Foddy. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Getting_Over_It_with_Bennett_Foddy

- Hayes, S. C., Strosahl, K. D., & Wilson, K. G. (2012). Acceptance and commitment therapy: The process and practice of mindful change (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

- Janse, B. (2022). ASE model (De Vries). Toolshero. Retrieved from https://www.toolshero.com/psychology/ase-model-vries/

- Nagorsky E, Wiemeyer J (2020) The structure of performance and training in esports. PLoS ONE 15(8): e0237584. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0237584

- Pearson. (n.d.). Cogmed Working Memory Training [Software]. https://www.pearsonassessments.com/

- Pillow Castle Games. (2019). Superliminal [Video game]. Pillow Castle Games.

- Rotter, J. B. (1954). Social learning and clinical psychology. New York: Prentice-Hall.

- Schulze, J. (2024). The coach and enemy voice in Mindform: A psychological perspective. Esport Team Twente, Enschede, Nederland.

- Statespace. (2020). Aimlabs [Video game].

- Truby, J. (2007). The anatomy of story: 22 steps to becoming a master storyteller. Faber and Faber.

- U3170940. (2020). ACT BIF hexaflex [Image]. Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:ACT_hexaflex3.png

- Unity Technologies. Unity [Software]. Available from https://unity.com/

- Wreden, D., & Pugh, W. (2013). The Stanley Parable [Video game]. Galactic Cafe. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Stanley_Parable

Discover Mindform on Steam

Dive deep into the world of esports with Mindform, now available on Steam. Experience the journey, sharpen your skills, and cultivate the mindset of a champion. The arena awaits!